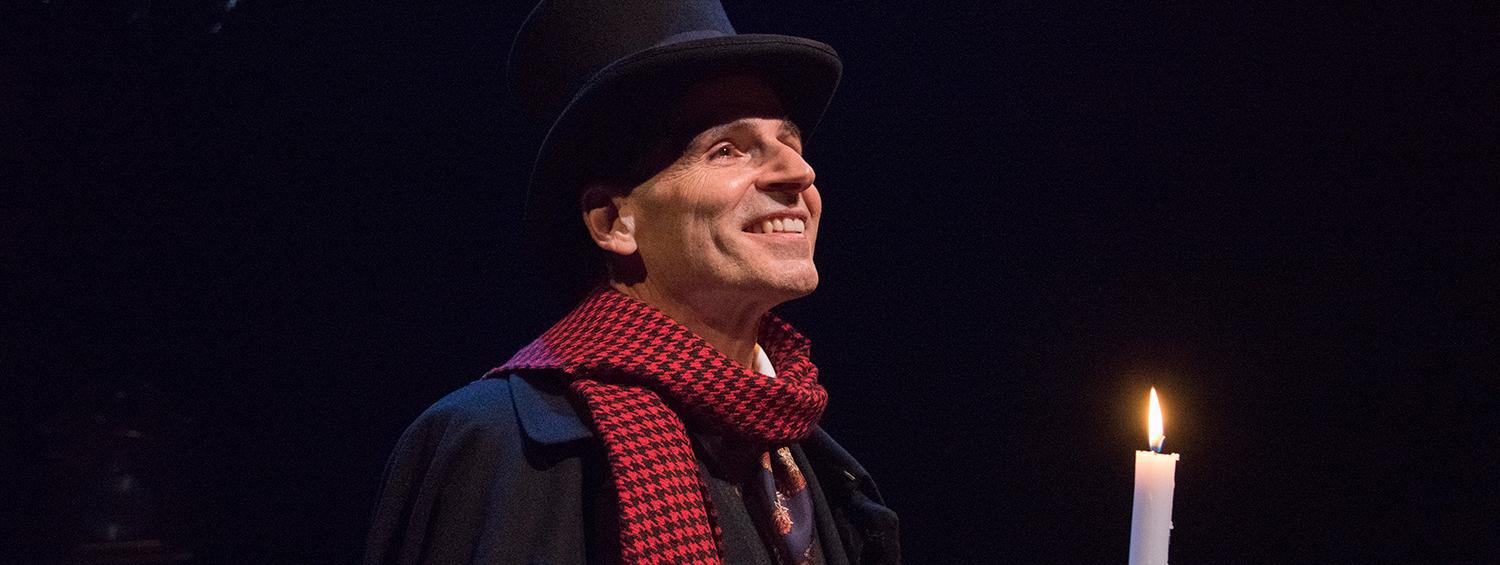

The holiday season is full of a wide variety of traditions, and Olney Theatre Center’s one-man production of A Christmas Carol, now in its 14th year, is one of many. For both performer Paul Morella and audiences alike, the story of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol is one that brings them back year after year. But there are so many productions and adaptations of the story - what is it about the story that makes people keep coming back to it? And how has Morella’s production solidified itself as a tradition that audiences return to year after year?

Morella explained, “One of the ways this production has grown over the years is the fact that people come, people come back, people tell people about it, people bring people with them, so there’s this wonderful mix of people who have been there a number of times and people who are there for the first time. And hopefully, they become converts as well and then spread the word, what I like to refer to as ‘The Gospel According to Dickens.’”

Image credit

Image credit

Over the years, Morella has made small tweaks and changes to the production, always looking to improve and provide a new experience for repeat audience members. Morella describes putting on this production of A Christmas Carol as “a year-round thing.” He adds “Once it ends, it's always in the background in terms of what could be different next time, or what can be explored, and how can this be enriched? It's like archeology in a lot of ways, continuing to dig deeper.” In making these changes, Morella will, every year, “watch as many [different versions] as he can, he will listen to as many audiobooks as he can of the full text, just to hear if there’s a passage that he would like to try to get in, or somehow to sort of alter a little bit of the script.” The adaptations can prove fruitful, as Morella says, “I think there is something to be gleaned in every product that is out there, something that can be learned. Even The Muppets’ Christmas Carol was a big influence on me, or Mr. Magoo's Christmas Carol, which actually uses some of the lines from the original text. It’s interesting how the heart of the story always remains the same, but I think there is enough to go around for everyone to sort of tinker and play with it.”

But this tinkering is not just unique to Morella or Olney’s production: even Dickens continued to edit the text. Morella discussed how Dickens only had six weeks to submit his initial text to be published, so the author used his reading tour, which he performed in England and throughout the United States (including a stop at Carroll Hall in Washington, DC in 1868) to edit and move things around. Just like the production here at Olney Theatre Center, the story was constantly evolving. Besides potentially altered text, the audience members may make a new version of the story for themselves, Morella has learned that “sometimes people who have been there before will find the current experience very different from the one they had previously, not because something has changed necessarily with the production but because they are in a different place, they’ve changed, and so they pick up on different things depending on where they are in their lives at that particular moment. Which I think is a testament to Dickens and to the story, how it continues to reinvent itself and reimagine itself and remains fresh and in the moment.”

Taking the idea of A Christmas Carol literally, Olney’s production leans into the musicality of Dickens’ text by telling the story exactly how the author originally intended for it to be told: by one person, just as he did on his tours. But in creating the production that is so recognizable for audiences today, Morella had to do a lot of brainstorming. Some initial ideas for the production were a foley artist at a radio station doing a production of A Christmas Carol over a broadcast after the cast members were snowed out, or even one with a grown-up Tiny Tim telling the story. But Morella kept finding himself coming back to the richness of the text: “I think this is a story that you could theoretically tell any time during the year. The themes are very rich, you know, the whole idea of redemption and things like that. It goes to the core of humanity in a lot of ways and how we are all in this together. I think sometimes people make the mistake of assuming that this is a religious story or allegory, and it really isn't. So it can appeal to all faiths - or non-faiths even - because it's about what we do with the time we have on this planet and how we make the most of it.” The text also works so well in this version because of what Morella refers to as “experiential storytelling,” where the audience and the performer or narrator get to experience the story together, rather than the narrator simply telling the audience what happens.

Image credit

Image credit

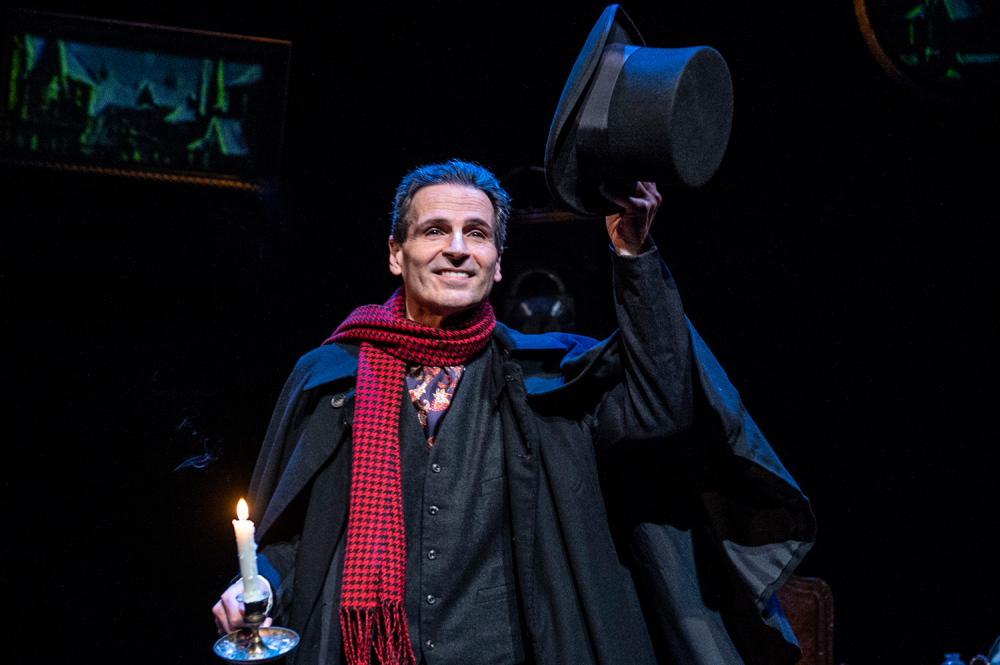

Everyone is a participant and collaborator on that specific performance, and as Morella explained, Dickens’ text seamlessly allows for this to happen: “It’s difficult to wrap your mind around how it can work with one person, but one of the things I find very fulfilling is the fact that sometimes when people come in and they can’t figure out how this is going to work, and then when they leave (and again I’m there on the way out so they get to share their experiences there), they’ll tell me that they can’t imagine it any other way because of the magic that he has sort of works with this particular production. And having the luxury of working on something for this long is you get to really dig deep and it’s so much further beyond just learning the lines and things like that. There are a lot of lines, and I think people are very intrigued by that fact. That’s one of the questions on the way out is “how do you remember all these things” but as far as Dickens is concerned, he does a lot of that work for you because there’s a musicality to the language, there’s a rhythm and cadence, it is like a song, it is like a carol - a long one. But it follows a thought process and because its first person narrative it really works and it really kind of lands, these words sort of assimilate, and it’s not something that there's a struggle to retain that.”

Beyond any production element or textual interpretation, one of the most memorable aspects of the show is how Morella personally greets each audience member at the door, and bids each farewell as they exit. Morella explains, “That was not something that was a conscious choice when I first workshopped the production before it came to Olney. I couldn’t afford to hire anybody to take tickets or to be there when they left, so I did it. And it was something that we thought fortuitously or serendipitously that we should keep because it was a great way to kind of contribute to the informality of the whole evening, and that way I get to sort of interact with the audience and that’s where they get to tell me how many times they’ve been there, it’s great to be back, and what the show means to them, which I think is a really really important part of the whole experience and something that you don’t normally get in a theatre production. Usually, there’s that separation between the performers and the audience, and I think that this gives them the opportunity to contribute and collaborate and share what it means to them and what appeals to them and what the experience is like. [...] In those moments, it’s really something special, unique, and rare I think. It’s certainly something that I’ve never experienced in my 40+ years being a professional actor.”