Stephen Karam initially set out to write a thriller when he began work on The Humans but wound up writing about a family dinner. For Thanksgiving this year, the Blake family gathers at the youngest daughter’s recently acquired Manhattan apartment, but a mysterious thud from the upstairs neighbor continually interrupts the evening. This completely mundane sound becomes increasingly disturbing as the evening progresses, but it’s difficult to say why. The Humans elicits a growing sense of anxiety and dread, but the source of the particular type of fear in this play is nothing strange or spectacular. Instead, it grows from something uncannily familiar: the fragility and instability of everyday life.

Stephen Karam begins his play with several epigraphs; the first comes from Napoleon Hill’s 1930s Think and Grow Rich. In the quote, Hill lists six basic fears which everyone suffers at one point or another. He identifies them as the fear of poverty, criticism, ill health, loss of love of someone, old age, and death. These fears are what Karam calls “basement-level fears”: common anxieties and worries most people repress so they can carry on with the business of everyday life.

Each of the Blakes displays one or more of these fears manifested through job loss, biting comments, betrayal, mental and physical illness, failure, and fractured relationships. The horror of this play is not a result of anything supernatural, but the ordinary troubles of six nuanced and complicated humans. They spend most of the evening skipping around these anxieties and doing their best to have a pleasant family evening. However, as Stephen Karam noted, “no matter how hard we try to repress [these fears], they eventually creep into the light, sometimes in fantastic disguise.”

In a second epigraph, Karam invokes Sigmund Freud’s essay The Uncanny. In this essay, Freud dissects the feeling of the uncanny and questions why some stories invoke more dread than others. He concludes that the uncanny is both “something familiar which has been repressed” and that which “ought to have remained hidden and secret, and yet comes to light.” The characters in The Humans are instantly recognizable. They could be one’s neighbors, friends, or family and the storms they weather are well-known. That familiarity is what makes this play so uncanny. The Blakes depict with specificity and accuracy the type of anxiety most try to avoid confronting. They achieve a certain universality, standing in for an increasingly unsteady world.

Karam began writing The Humans in 2014 to “try and locate the black pit of dread and malaise Americans have been trying to climb out of post-9/11 and post-financial crisis.” When OTC decided to produce The Humans in the 2019-2020 season, we had no idea how relevant the anxieties of this play would become. The COVID-19 outbreak has taken a toll on America’s collective sense of stability and exposed the fragile structures of daily life. Stress about health, losing loved ones, isolation, employment, and finances are prominent for a large portion of Americans now more than ever.

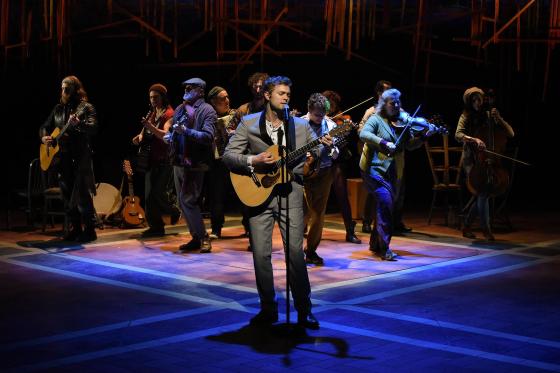

But this play is not just about dread. Despite the loud thuds and creeping worry, The Humans is just as amusing in its familiarity as it is uncanny. The family bickers and forgives, persisting through the anxiety by clinging to each other for support. As much as this play confronts the presence of fear in everyday life, it also shows how people cope, move on, and live their lives in spite of it. In a New York Times profile, writer Alexis Soloski describes Karam as a playwright who “specializes in painful comedies that really shouldn’t be as funny as they are.” In one moment, this play looks over its shoulder to worry about what might be lurking outside the door but in the next creates moments of relief and laughter. In this paradox, The Humans depicts the reality of life with frightening accuracy and cheerful humanity.