Thomas Edison’s company revealed the first sound recording device—the phonograph— in 1887 and a year later debuted the first motion picture camera. Edison predicted their combined use, commenting in Scientific American, “It is already possible by ingenious optical contrivances to throw stereoscopic photographs of people on screens in full view of an audience. Add the talking phonograph to counterfeit their voices, and it would be difficult to carry the illusion of real presence much further.” He wasn’t wrong, but the world would wait 50 years before synchronized sound in film became practical enough for commercial use.

Singin’ in the Rain implies The Jazz Singer was the first motion picture with dialogue (also called talkies). However, In the half-century between the invention of the phonograph and The Jazz Singer, many innovators successfully paired sound with film. These attempts did not have enduring commercial success due to three major obstacles: cost, synchronization, and amplification.

While possible, synchronization was demanding and fraught with error. In 1900, Clément Maurice Gratioulet and Henri Lioret established the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre in Paris and began showing films of famous Parisian singers and comedians. They achieved synchronization by manually adjusting the speed of a hand-cranked projector to match the speed of the sound. The projectionist at the back of the theatre used a telephone to listen to the phonograph in the orchestra. The process was imperfect and relied on the projectionist’s timing, and the theater was only commercially successful for a few years before audiences lost interest.

Those experimenting with sound relied on the phonograph, but the device was not capable of projecting to an entire audience. Léon Gaumont invented the Elgéphone in 1906, which amplified sound with compressed air but was bulky, expensive, and unreliable. Gaumont unsuccessfully marketed his solution to theatres unwilling to take the financial risk. Electronic amplification would eventually solve this problem, but not for another decade.

Film and sound had already developed two separate and successful entertainment industries, so most studios saw the addition of sound as unnecessary. Movies already had sound accompaniment in the form of live musicians. Even the smallest movie theatre had a single pianist creating appropriate mood music for each film; large movie theatres would sometimes have a full 72 piece orchestra. Examples like Auguste Baron, who in 1896 sank his fortune into creating three talking movies and ended up bankrupt, deterred most studios from experimenting with the technology. Sound film was something of a financial black hole.

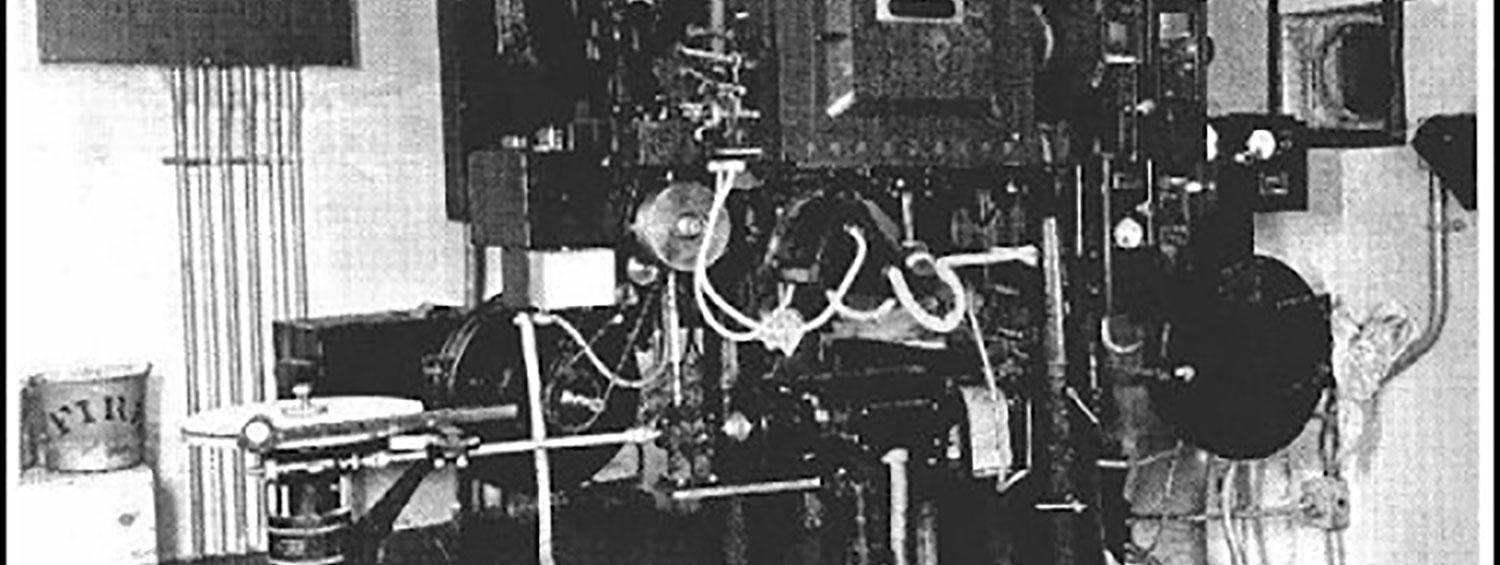

The right combination of technology and financial opportunity came together in 1922 when Western Electric perfected its system of amplifying and synchronizing sound for film. They sold this technology to the rapidly expanding Warner Brothers Studios. Sam Warner convinced his brothers to buy into the system and spent the next few years developing the Vitaphone with Western Electric. However, the Warner Brothers, like most major studios at the time, believed that audiences did not want to hear dialogue in film. For a few years, Warner Brothers used the Vitaphone to release movies with a pre-recorded music so smaller theaters that previously relied on a single pianist could now have full orchestra accompaniment. The 1926 release of Don Juan with a pre recorded soundtrack, including some sound effects like clashing swords, was a massive success. A year later, The Jazz Singer included some small, incidental scenes of Al Johnson speaking in between musical numbers and famously saying “You ain’t heard nothing yet.” The rest of the dialogue played out with inter-titles like a silent film. An overwhelming positive reaction to the talking scenes convinced studios to produce more talkies. The next year, Warner Brothers released their first all-talking feature-length film, Lights of New York.

Talkies rapidly replaced silent movies, and from 1927 - 1930 the film industry need to adapt. During the silent movie era, cameras were loud, directors shouted while filming, and performers focused on physical expression. All of these things had to change with microphones on set. Early microphones were limited, but extremely sensitive to sound within their range. As accurately portrayed in Singin’ in the Rain, microphones were hidden on set and needed to be spoken into directly. Cameras and camera operators were enclosed in booths, making moving the camera next to impossible. Actors and actresses accustomed to large exaggerated gestures had to minimize movement. Also, the Vitaphone recorded film and sound on seperate devices, so film could not be edited without desynchronizing the sound. The combination of these obstacles made the early sound films resemble recorded stage shows.

It is true that some stars could not adapt to the new style of movie making. The transition was so stressful for the movie industry that gossip magazines called the transition the “Talkie Terror.” German actor Emil Jannings could no longer find work in the United States because of his accent. Due to a childhood throat injury, comic actor Raymond Griffith could only speak in a hoarse whisper barely audible to a microphone. Other actors/actresses completely altered their career. Reginald Denny, a British actor known for playing leading American men, transitioned to character roles. Physical actors like Douglas Fairbanks were now restricted to a stiff, motionless style. In 1920, actress Clara Bow told Motion Picture Classic magazine that talkies were “stiff and limiting... there’s no chance for action, and action is the most important thing to me. [But] I can't buck progress. I have to do the best I can.” However, some actors/actresses thrived during this time. Mary Pickford had been an actress for thirty years before talkies and won an Oscar for her first speaking role.

Despite the aggressive changes, sound in film likely saved the industry during the Great Depression. Throughout the ‘20s, film attendance declined. After the introduction of sound, weekly movie attendance rose from 57 million in 1927 to 95 million in 1929. Technology rapidly developed around sound films to allow filmmakers more freedom. Cameras became quieter, microphones improved, and by 1930, most studios switched to sound-on-film technology which allowed editing. A new era of storytelling began.