Learn about the inspiration behind Lautrec at the St. James, a new musical a part of the Applause Concert Series.

The Time

LAUTREC AT THE ST. JAMES takes place in 1899 during a period known as the Belle Époque. It was a period between the Franco-Prussian War and World War I, 1871- 1914, when much of Europe enjoyed a period of peace, prosperity, optimism, rapid developments in science and technology, and relative political stability. It was "the beautiful era," a golden age, a time best characterized by the expression joie de vivre (from the title of a book by Émile Zola). With this prosperity and the ascension of the Third Republic in France, La Belle Époque also sponsored a remarkable renaissance in the visual arts. Impressionism laid the groundwork in the 1870s and 1880s in works by Monet, Renoir, and Sisley. By the 1890s, such Postimpressionist masters as Cézanne, Matisse, Gauguin, and Toulouse-Lautrec had found their patrons. These artists were the vanguard of modernism in painting, a new freedom within the medium that inspired similar experimentation in all the arts.

Paris hosted the World's Fair in 1889 with its great exclamation mark, the newly constructed Eiffel Tower serving as the beacon in a world of new possibilities. Georges-Eugène Haussmann's redesign of Paris was nearly complete. By then, the Moulin Rouge and the Folies Bergère also were open for business. Hosting another World's Fair in 1900, Paris seemed, indeed, the place to be.

The Characters

Most of the characters in Lautrec at the St. James are based on real people. The exceptions are Simone, Nina, & Rosa who are based on the prostitutes he became closely acquainted with while living amongst them in the brothels.

The character Claire was inspired by an actual much younger cousin of Lautrec’s who never “looked at him differently.” They adored each other to the point that her parents became concerned and took precautions to distance the two. (Remember at that time cousins often married, an example, his own parents.) Our Claire is young, not naïve, but yet has an untainted perspective on life and an openness to both experience and people. She has seen enough at her young age to be well aware of how the world operates, and survive in it, but not beaten down by it. Henri sees a purity and honesty in her. (As he would have with the cousin)

Lautrec did have a “keeper” in the asylum thus the inspiration for Edouard. He is present in almost every scene, thus the great observer. Through observation, and little said, he comes to “know” and ultimately truly understand Lautrec. And, as he witnesses Lautrec’s hallucinatory moments, and what Lautrec seems to be experiencing, they become almost vivid for Edouard as well, where he can actually begin to fully imagine them. The idea that when someone is an excellent storyteller, we ourselves can feel transported and visualize everything.

Henri de Toulouse Lautrec

An aristocratic, alcoholic dwarf known for his louche lifestyle, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec created art that was inseparable from his legendary life. His career lasted just over a decade and coincided with two major developments in late nineteenth-century Paris: the birth of modern printmaking and the explosion of nightlife culture. Lautrec’s posters promoted Montmartre entertainers as celebrities and elevated the popular medium of the advertising lithograph to the realm of high art. His paintings of dance hall performers and prostitutes are personal and humanistic, revealing the sadness and humor hidden beneath rice powder and gaslights. Though he died tragically young (at age thirty-six) due to complications from alcoholism and syphilis, his influence was long-lasting. It is fair to say that without Lautrec, there would be no Andy Warhol.

Lautrec began drawing at a young age when frequent illnesses (portending more serious health problems to come) kept him bedridden at the family estate in Albi in southern France. Due to a genetic weakness resulting from the consanguineous marriage of his parents (who were first cousins), Lautrec’s legs ceased growing after he broke both his femur bones in separate, minor accidents during his adolescence. As an adult, Lautrec had a normally proportioned upper body but the stubby legs of a dwarf; his mature height was barely five feet, and he walked with great difficulty using a cane. Lautrec compensated for his physical deformities with alcohol and an acerbic, self-deprecating wit. His sympathetic fascination with the marginal in society, as well as his keen caricaturist’s eye, may be partly explained by his own physical handicap.

In 1882, Lautrec moved from Albi to Paris, where he studied art in the ateliers of two academic painters, Léon Bonnat (1833–1922) and Fernand Cormon (1845–1924), who also taught Émile Bernard (1868–1941) and Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). Lautrec soon began painting en plein air in the manner of the Impressionists.

Lautrec eventually established himself as the premier poster artist of Paris and was often commissioned to advertise famous performers in his prints. One of Lautrec’s favorite café-concert stars was Yvette Guilbert, who was known as a diseuse, or “speaker,” for the way she half-sung, halfspoke her songs during performances. She had bright red hair, thin lips, a tall gaunt physique, and wore black elbow-length gloves. By exaggerating the characteristic features of these women, Lautrec conveyed the essence of their personalities.

The style and content of Lautrec’s posters were heavily influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e prints. Areas of flat color bound by strong outlines, silhouettes, cropped compositions, and oblique angles are all typical of woodblock prints by artists like Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858).

Lautrec’s prints often display dazzling technical effects, as new innovations in lithography during the late nineteenth century permitted larger prints, more varied colors, and nuanced textures. Indeed, the directness and honesty of his work testify to Lautrec’s love of women, whether fabulous or fallen, and demonstrates his generosity and sympathy toward them.

His short stature of 4 ft 8, meant that Toulouse-Lautrec often felt, and was treated like, an outsider. He felt comfortable in the company of those on the margins of society who were otherwise deemed unsavory, such as circus performers, dancers, and prostitutes. Through these sordid social circles he created some of his most remarkable pieces of art, capturing the vibrancy of the mix of classes and cultures in the French cafés. His height also meant that he could often observe others unnoticed allowing him to incorporate a narrative energy into his art: even in crowd scenes each figure is highly individualized.

In 1899, his health failing from the effects of alcoholism and syphilis, Lautrec was institutionalized for several months at an asylum near Paris, where he produced a remarkable group of drawings of the circus, drawn from memory. Soon after his release he returned to drinking, and his artistic production dropped significantly. In 1901 he suffered a stroke and died two months before his thirty-seventh birthday at his mother's estate, the Château de Malromé. He left behind 737 canvased paintings, 275 watercolors, 363 prints and posters, and 5,084 drawings.

Our story focuses primarily on the series of months when he was institutionalized against his will. The asylum, the St. James, was more what today we would consider a rehab facility, but the clientele was certainly mixed in terms of their afflictions or diseases. A side effect of syphilis are hallucinations and in this moment of Lautrec hitting rock bottom and having to question so much about his past, future, and talent, the hallucinations become a means for him to face his existence, the choices he has made, and the consequences of his actions. He is about to potentially lose both his greatest passion, and his identity, which is his art. Ultimately raising the question, how much would one be willing to sacrifice for their passion? Would one die for it? As previously mentioned, due to his appearance, he had lived his life with the stigma of being an outsider, disabled in an unsympathetic time period, which caused him to believe that he could never be truly or completely loved. Thus, he had an enormous fascination with love, and in his role as observer and artist, sought out places and people where love was being defined in more unconventional ways such as in lesbian nightclubs or in brothels. He was obsessed with the interaction between lovers; affection, touching, things that were never naturally given to him. Also, due to his appearance, and because attention was naturally drawn to him because of it, his humor was often self-deprecating, his goal was to be the life of the party, to have the last laugh, seeking out popularity, friendship, sentiment, attachment through other means.

As a character in our story, due to his physical & mental condition as a result of the syphilis, alcoholism, and the recovery process, he has mood swings ranging from rage to tenderness. He should be unpredictable, partly because the world he is existing in at the asylum is completely unpredictable. He experiences emotions at their extremes, not only as result of the illnesses but from the accumulation of horrific obstacles facing him; the fear of losing his talent, of losing his status as an artist, being considered a lunatic and shunned by society completely, of forever being institutionalized, at the mercy of his Mother signing the release to his freedom, and dying.

Misia and Henri are two people who truly understand each other, they “get” each other. Their relationship is rooted in this; in sincere caring, in always being truthful with the other (brutally if necessary), and respecting one another on an artistic level. He sincerely loves her, but it’s a love that can never be.

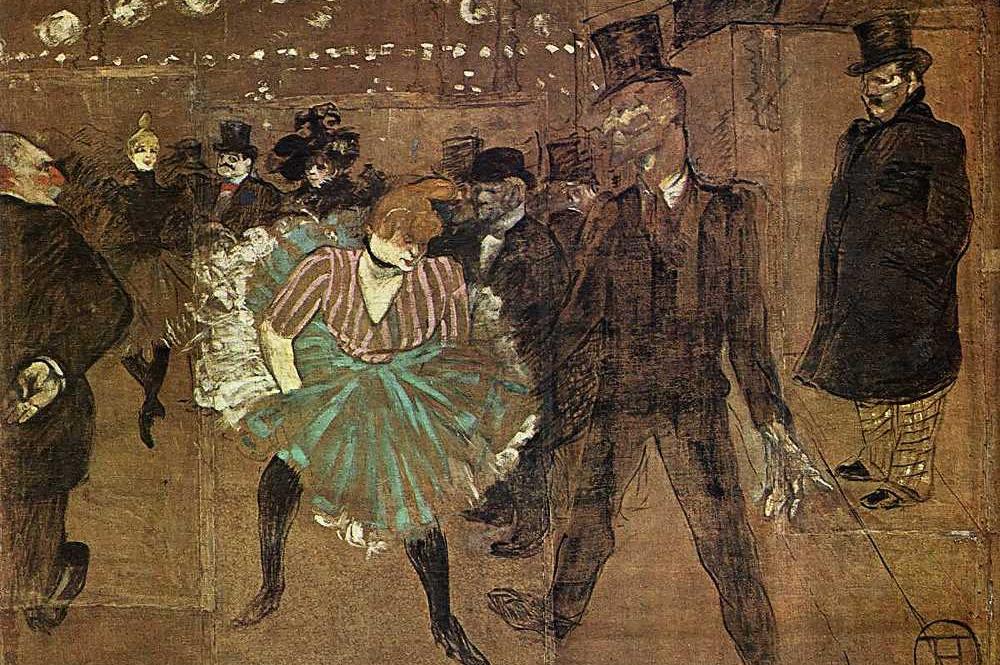

Dancing at the Moulin Rouge: La Goulue and Valentin the Contortionist, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, ca. 1895

Misia Natanson (Husband - Thadee Natanson)

Patron of the arts, matchmaker, tastemaker, collector, muse. Misia Sert, née Godebska, at a time when Paris was truly the brash, beating heart of the art world, was a kingmaker, holding court. Though it is stated that Misia "did not create anything,” her magnetic allure moved others to create near her, or for her, or about her, through heady eras—from the Belle Époque 1890s through the 1930s—and across disciplines: art, music, literature, dance, theater, fashion. Modern and timeless, imperious and vulnerable, vivacious and enigmatic, but more charismatic than beautiful, she was one of the most prolifically painted women of her time. A gifted pianist, she had a keen ear for avant-garde talent, rescuing masterpieces from anonymity, fiercely boosting her favorites. Dinners chez Misia were coveted affairs, from titled nobility to teenage poets.

Marcel Proust called her "a monument of history," finding inspiration for two characters in his magnum opus In Search of Lost Time: a meddling madame and a young princess "sponsor of all these great men." The pianist Erik Satie, who dedicated his "Three Pieces in the Shape of a Pear" to her, called Misia "a magician." She gave her catty confidante (and rumored lover) the young Coco Chanel an entrée into the art world.

Misia was born in St. Petersburg in 1872. Her mother died in childbirth, after racing from Belgium, heavily pregnant, into a harsh Russian winter to confront Misia's sculptor father, Cyprien Godebski, and his mistress. Misia would always be drawn to similarly brilliant, selfish figures. She said she had "only husbands, never lovers" and would divorce three times, childless; each relationship's sordid, thrashing end became a trove of material picked over by artists.

Although raised in Belgium and France, she was called "La Polonaise" for her father's roots, her Slavic features and her black-eyed exotic charm. Her grandfather was a leading cellist and she studied piano under the composer Gabriel Fauré. As a child, she impressed Franz Liszt when she played Beethoven while seated upon his lap.

In 1893 she married Thadée Natanson, who led the progressive literary journal La Revue Blanche, a Belle Époque hotbed of young unknowns poised to change the face of art, music, and literature. He was older and for her it was a love out of admiration and idolization. This was period of education for her, and his world, and its inhabitants, were the educator. An intimate circle of composers, painters, and poets would linger at the Natansons' stylish apartment on the rue Saint-Florentin and their summer homes outside Paris. Misia's biographers, the American pianists Arthur Gold and Robert Fizdale, called her "the feminine touchstone of one of the most talented circles of artists that Paris has ever known." They describe fin de siècle nights with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec at the Chat Noir, the Montmartre cabaret the artist immortalized, with Satie at the piano and Debussy brooding in a corner.

Toulouse-Lautrec, Vuillard, Bonnard, and Vallotton, all were more or less secretly in love with her, and would paint Misia in every light—at the piano, on the porch, having breakfast. Sweet and shy Vuillard fell hardest, and his Misia portraits and photographs were plentiful.

La Revue Blanche, and Misia's first marriage, couldn't last. Natanson turned to business to shake the journal's debts, eventually pushing his wife into the arms of a wealthy creditor, Alfred Edwards (Barrett), the domineering newspaper tycoon she would marry in 1905. But her artistic influence only grew. With the playwright Octave Mirbeau, Natanson would allegorize the couple's end in the controversial Le Foyer, staged at the Comédie Française. And Misia happily supported artists with Edwards's money. She gave Renoir 10,000 francs for her portrait, luminescent in pink and pearls with a little dog under her arm. It was as much as the master would accept—a trick she would use again to help proud, needy artists like Stravinsky, well after Edwards left Misia for a nubile bisexual actress.

Her third husband, the Catalan painter Josep Maria Sert, exposed her to a new avant-garde world. (The massive American Progress mural in the lobby at 30 Rockefeller Center is his.) Misia grew close to the Russian impresario Serge Diaghilev, financing his Ballets Russes, even rescuing imperiled performances with cash before curtain. She was present at the creation of their most scandalous successes: Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (1913), a seminal piece that Misia's savvy saved from a reticent Diaghilev; and the Satie-Cocteau cubist ballet Parade (1917), Picasso's foray into set and costume design. Misia had introduced Diaghilev to Cocteau, and was later godmother to Picasso's son, Paolo.

Jean Cocteau's novel Thomas the Impostor models a princess on Misia and her World War I adventures. She had appealed to couture houses for delivery trucks and, with Cocteau and Sert, ferried casualties from the front. Much later, Cocteau's 1940 ménage-à-trois play The Sacred Monsters flowed from the murky, claustrophobic trio Misia and Sert formed for years with a Georgian princess 30 years their junior, for whom Sert would eventually leave Misia, crushing her spirit.

Late in life, going blind and addicted to morphine, Misia made drug runs to Switzerland with Chanel, the last brilliant tyrant she loved. Photos of her last trip to Venice in 1947 show Misia as slight but still regal-looking. When she died in Paris in 1950, Chanel laid out her body on a bed of flowers, a work of art at the end.

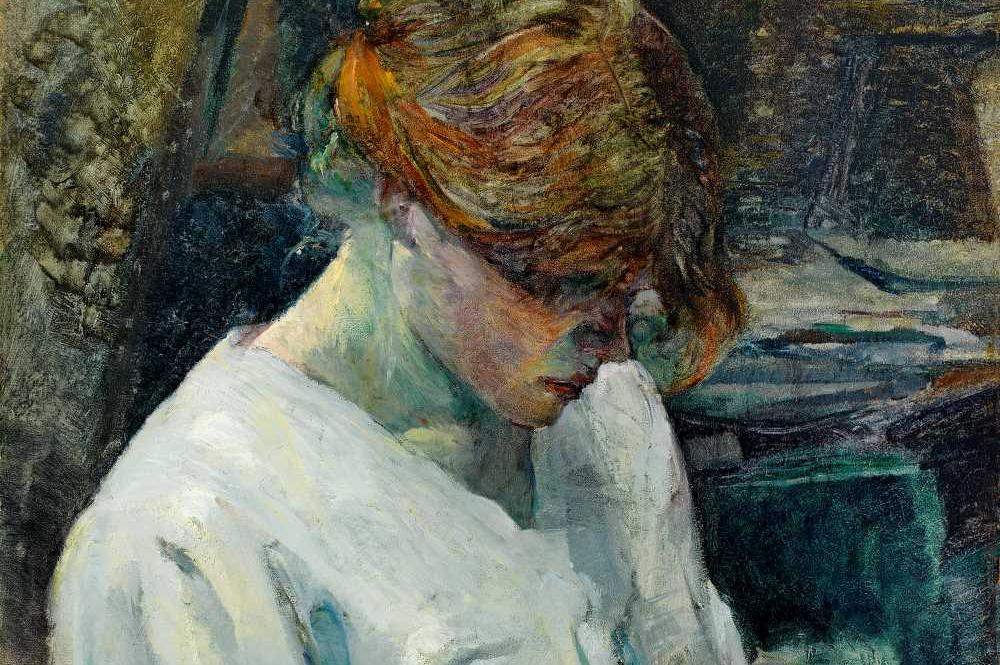

The Red-Head in a White Blouse, by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, ca. 1889

Countess Adéle de Toulouse-Lautrec

Lautrec’s mother Adéle came from an old family from the Aude province. The two familes, Toulouse-Lautrec and Céleyran, had been interrelated since the 18th century. Adéle married her first cousin, Count Alphonse-Charles-Marie de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa. Her second son, Richard, died 5 at the age of one, after which, Adéle fled with Henri, wanting nothing to do with her husband ever again. Her life was over, and from now on, Henri would be her sole consolation. Throughout his adolescence, through his illnesses and accidents and the realization regarding his disability, Adéle was a loving refuge. As he grew older, finding his vocation, and creating a life for himself in Paris, particularly Montmartre, as Lautrec described her, “my poor saintly mother,” was alarmed by the life he was leading. Her principles, religious faith, and respect for convention were all denigrated by it. Later, as Lautrec became for famous and the subject matter of his work more controversial, when asked “who is your favorite painter?” she stated, “Certainly not my son.” Despite her judgement and disapproval, she remained steadfastly devoted to him and his well-being.

NOTE: Alfred Barrett, in real life, is Alfred Edwards, Misia’s second husband. We changed the name because it was too similar to and could be confused with Edouard.