Meredith Willson’s The Music Man begins with the iconic number “Rock Island,” a rhythmic patter number that speeds up and slows down over the course of a train ride. In the song, a group of traveling salesmen lament about the changing times and how their individual business practices have been affected by the introduction of taking cash instead of working off a credit line. But what exactly is a traveling salesman and why are the traveling salesmen we meet in the first scene of The Music Man so fed up with the way that the infamous Harold Hill runs his business?

What is a traveling salesman?

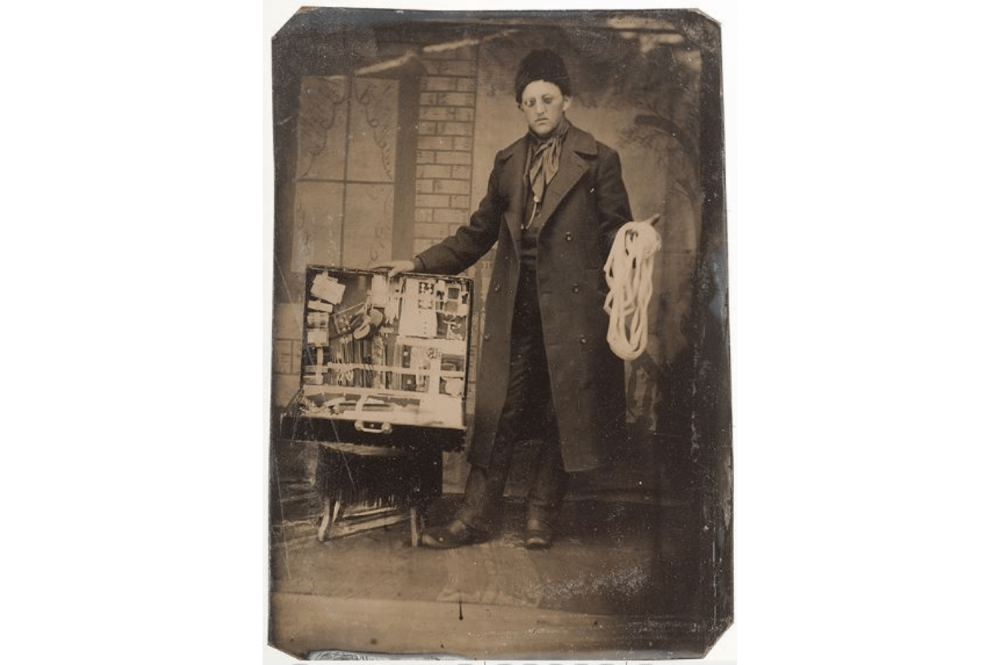

While traveling merchants and peddlers have existed for centuries, the heyday of the “traveling salesman” took root in the 19th century. Unlike the trade merchants of Great Britain and Germany, who manufactured goods on a smaller scale established by their own craftwork traditions, American manufacturing and salesmanship in the 19th century exploded due to rapid manufacturing and relatively loose class restrictions. According to Harvard Business School’s Walter A. Friedman, author of Birth of a Salesman, the factors that led to this traveling salesman revolution were, “a stable currency, the rule of law, the protection of private property, and the availability of credit.” The salesman revolution changed nearly every inch of the country. Communities became “territories,” people became “targets,” and merchants became “salesmen.” Essentially, America in the 19th century had the resources and workforce to manufacture an abundance of goods, and there was a need to create a demand for products. This is where the traveling salesman comes in.

Traveling salesmen were representatives of a company that were assigned a ”territory” and tasked with selling as many of the company’s manufactured goods as they could within that area. Their income was based on a commission pay structure, so the goal to sell as many manufactured goods as possible often superseded the desire to cater to the territory's true needs. Combine that with the new rail system that allowed quicker travel across city and state lines, and the traveling salesman had the upper hand. If you were good at your job, you got to know your territory, sold as much as possible, and moved onto the next town after establishing a credit line with customers. The ease of travel and not having to wait for cash before counting a sale meant that these salesmen were able to do their job effectively, driving up the demand for these surplus manufactured goods.

The "Hill" Problem

There were not many systems in place to verify a traveling salesman’s identity. Though the train system connected towns, news still traveled slowly as local papers were centralized to their own town affairs. If desired, a salesman could waltz into each town with a new identity and a story that best benefited their sales pitch. That’s exactly what Harold Hill does in The Music Man. In each new town, he changes his identity to be sure that his reputation does not proceed him by word of mouth and in order to be most impressive to the townspeople he’s trying to appeal to. Meredith Willson is playing off a reputation that traveling salesmen gained in the early 20th century, and taking it a step further. Salesmen were known to embellish, make up stories, and lie in order to sell their goods. In a PBS article titled The Business of Direct Selling, traveling salesmen are described as having become “a familiar -- and sometimes comical -- image in America. Salesmen were considered slick and untrustworthy, peddling cure-all elixirs and overpriced Bibles.”

Traveling salesmen still exist today, but their prominence in modern business strategies has waned. The introduction of mass advertising campaigns and a more efficient transportation systems changed the game. The methods businesses used to hit their quotas outgrew the need for individual traveling salesmen. However, one could argue that in the 21st century there has been a resurgence of the traveling salesman archetype with the rise of social media influencers. Similar to how traveling salesmen were able to carefully construct their identities in new towns, the internet personas that influencers create are characters that can be wholly separate from reality. Brands are now electing to work with individuals once again to push demand for their products, electing to hire influencers to create relatable content online, sometimes interweaving the advertisement into a “day in the life” video. This style of marketing is often criticized for being disingenuous, as content creators are paid to say only positive things about the products. Some creators have even been embroiled in “scandals” for pushing products that were ultimately faulty or low quality. And at the end of the day, the mantra from their 19th century counterparts remains the same, “Sell Sell Sell.”