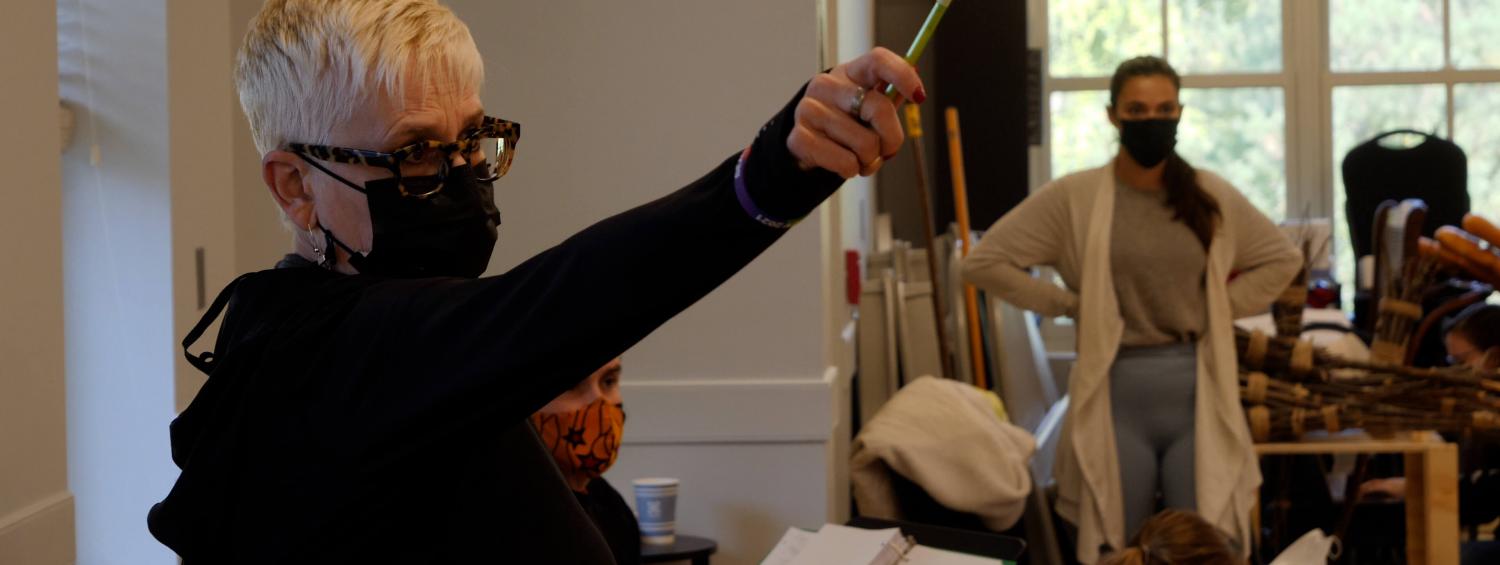

Alissa Klusky, Production Dramaturg, sat down with the director of Disney's Beauty and the Beast, Marcia Milgrom Dodge to talk about her vision for the production.

Alissa Klusky: Hi Marcia!

Marcia Milgrom Dodge: Hi Alissa!

AK: So lovely to sit down with you today to chat about Olney Theatre Center’s production of Beauty and the Beast. I know your first time directing at Olney was Once in 2018, and that production was nominated for a Helen Hayes Award! What was your initial reaction when you were approached by Artistic Director, Jason Loewith, to come back and direct Beauty and the Beast?

MMD: Well first of all, I am the girl who can’t say no. So, I’ll say yes, and then I’ll say “oh no, what did I just say yes to?” I was thrilled to be invited back. I had such a beautiful time with Once; it was a really transcendent experience to be around that music with that company and to tell that story. So, when Jason said: “Do you want to do Beauty and the Beast? It’s our big show for the season.” I was like “YES!” And then I thought...I think I must go digging deep and wrestling with this text. And think about how to make it resonate with an audience in 2021, post pandemic shut-down. You know, what is our world like right now?

It’s very important to me that stories reflect our communities and our culture and the world that we’re living in now, and that there’s some real reason to do the show. Besides the fact that it’s an award winning musical, considered a classic, and for me reimagining classics is kind of my raison d'etre [French for “reason for being”]. It became very clear to me once I started reading the script, that the casting was going to be crucial for this storytelling today. It was my husband, Tony, who I will credit, very boldly, who said “Jade Jones.” That’s it! That’s how we tell the story. And then we started to talk about the Beast, it gnawed at me that this Prince was so arrogant and mean to this Beggar Woman. This is a boy who lives in a castle with no parental units. Maybe there was some tragedy that caused the parent’s demise and caused the prince to have some impairment. I wondered if Evan Ruggiero could do this role; was he available? And he was! Once we found our Beast and our Belle, I thought this is the way we start to expand the definition of beauty for the 21st century. It was so thrilling for me to then dig into the script knowing who those actors were going to be inhabiting those roles. It really was kind of an outside-in process, because I knew I had to find my Belle, and find my Beast before we could really start this process.

AK: Beauty and the Beast was initially planned for Olney Theatre Center’s 2020-2021 season. The pandemic put everything on pause, but here we are a year later, putting on this magical musical. How did your vision for the show change in that time?

MMD: I’m so proud to say that our choices for casting occurred prior to the pandemic. In fact, Evan was cast on March 11th, 2020. He said “Yes!” and then the whole world shut down. So, it gave us an opportunity to bring Jade and Evan in as stronger collaborators. I don’t think in American theatre that we do that enough, where we cast our principals and construct the world of the play to serve them. That opportunity to me is such a treat and very rare. So, what the pandemic did for us in a positive way, is give us more time. We could really navigate the whole world of the set, make sure we were supporting our actors;, make sure that anything that was depicted on the stage was in service to their physicality and their abilities. And making what will seem like treacherous locales, in the moments we want them to appear treacherous, are in reality incredibly safe and accessible for both those actors.

Additionally, in the script, traditionally in Beauty and the Beast, there are physical depictions of corbels which are pedestals that hold up ceilings. Traditionally, in places like this that have prestige, they have a neoclassic female form carved into them. We knew after casting Jade, that classical Western depictions of female form didn’t jive with who our Belle was. So, we deconstructed them, and made them decorative without being human forms. They still serve a function in the castle, giving it the prestige and the grandeur, but we were able to examine “why does it have to be a female form?” Our definition of beauty is expanding, and our corbel wouldn’t look like that. So that was a conversation we were able to have once we had more time. We would’ve probably come to the same conclusion, but it certainly made the conversation more invigorating, more essential, to have those conversations once we were paused.

AK: You have a reputation for tackling historic musicals with a lot of moving parts, and putting your own unique fingerprint on them. When approaching a show of this size, where do you begin?

MMD: Well, I have sort of co-opted this wonderful phrase that I heard Don Cheadle say about a film he was in recently, directed by Steven Soderbergh-- a caper film, a lot of fun and very entertaining, but “we like to smuggle in some deeper meaning.” And so that’s what I really do! I never had a little soundbite phrase for that before this.

With a show like Beauty and the Beast, not only am I digging into the title roles, but the character of Belle’s father, Maurice. We have a beautiful actor who comes from a Slavic ethnicity, and in the audition I said “Sasha, give me a little Russian dialect on Maurice.” And so all of a sudden, I was like aha! We’re going to smuggle in a little bit of immigration into our context; that Maurice is from another country and he’s trying to make good in this French provincial town. And everybody thinks he’s a little bit crazy, so why is he crazy? Maybe he has early Alzheimer’s, maybe there’s something that doesn’t have a name yet, that we in the 21st century can look at someone and say: Why does everybody think he’s crazy? He gets lost, he goes on a ride in the woods and he gets lost, he loses things. I started looking at articles of early dementia and early Alzheimers, reading about the symptoms. We’ve created this relationship between Maurice and Belle, that gives more context to the fact that she’s a caregiver as well as his daughter.

It’s not being rewritten; there’s no lyric changes; there’s no text changes. We are doing the play, but we are digging in and finding some deeper meaning in those relationships. I think it’s really powerful, and I think it will help give new context to lots of first time theatre goers who are coming to see themselves depicted on stage.

Image credit

Image credit

AK: We have an amazing cast assembled for this production, led by Jade Jones and Evan Ruggiero. How has it been to work with them in the room on these roles?

MMD: Jade was an offer pending an audition, we didn’t audition any other Belles. Working with Jade in this role has been wonderful; she is very thoughtful, unique in her authenticity, and we’re leaning into all of those aspects. We’re also navigating moments where she can be softer and more contemplative. And when she sings songs like “Home” and “A Change in Me,” I think people are going to really feel that yearning, and longing, in a very beautiful new way. We’ve all been sort of crying under our masks and getting goosebumps in rehearsal. And I just spent two days with Evan working on fight choreography with our Fight Director Robb Hunter, and Evan is game and willing and free and risky. One leg or two, this is a man who is a strong actor, who is making exciting choices, is living truthfully and is allowing us to examine and explore how this Beast behaves, retaliates, and retreats.

AK: One thing I’ve heard you say often in rehearsal, is that this production is for “children of all ages,” and that we should never lose sight of the childlike fun in this piece. What do you hope this show says to the inner child in all of us?

MMD: I want it to say that it’s a story that celebrates community, authenticity, acceptance, and kindness. We have no special effects director on this project. The special effects are coming from old fashioned theater craft, in lighting, scenery, choreography, and staging. I think that there’s access to our storytelling because it’s simpler. In a way, it allows every child in the audience, no matter how old they are, to fill in the blanks of their imagination. They can imagine their own sense of princesses, and beasts, and villains, and heroes. I think that’s what makes it an important event in the theatre community. We do everything we do, and it’s not complete without the audience. Because of the type of theatrical choices we’ve made in the set where we’re not lugging big pieces of scenery from scene to scene, it really makes our audience our partner in this journey. That’s really the core of my reimagining of this show. It’s a group effort. I think the most exciting theatre is when I find myself leaning in and wanting to peer into this world and be a part of it. That’s community. I don’t want to be didactic in my theatricality, but if this sparks conversation when people leave the theatre that’s great. I hope people see it with eyes wide open. Another mantra of mine is “surprising, yet inevitable.” This is something I heard Bob Fosse say about Fred Astaire’s dancing. When Fred picks up a hat rack and starts to dance with it, you gasp! And then when he starts to do this pas de deux with it, you sigh. So it’s a gasp and a sigh. That’s what drives me. That’s how I make the choices I make. I want you to gasp with wonder and surprise, and then sigh into “oh, that’s exactly how it’s supposed to be told.”